This guidance is issued jointly by the Department of Health and Social Care, the Welsh Government, the Department of Health Northern Ireland, Public Health England, NHS England and NHS Improvement and with the support of the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry.

Delivering Better Oral Health has been developed with the support of the 4 UK Chief Dental Officers.

Whilst this guidance seeks to ensure a consistent UK wide approach to prevention of oral diseases, some differences in operational delivery and organisational responsibilities may apply in Wales, Northern Ireland and England. In Scotland the guidance will be used to inform oral health improvement policy.

Smoking in the UK

Smoked tobacco in the form of cigarettes, pipes and cigars, together with all other forms of tobacco, present a major risk to oral health. The overall goal of the dental team is to help eliminate all forms of tobacco use. It’s worth highlighting at the outset that much of the tobacco research has been conducted in relation to cigarette smoking in adults and therefore this may be reflected in the terminology used, where evidence is presented in the summary tables (Chapter 2: Table 3) and in the text below.

Despite fewer people smoking, it remains the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the UK (1). Between 2016 and 2018, 77,600 deaths were attributable to smoking per year in England with comparable estimates of 5,000 deaths each year in Wales, 10,000 in Scotland and 2,300 in Northern Ireland (1). Furthermore, exposure to second-hand smoke (passive smoking) can lead to a range of diseases, many of which are fatal, with children especially vulnerable to the effects of passive smoking (2).

Smoking and other forms of tobacco have a significant impact on ill health and health inequalities. Tobacco use, including both smoked and smokeless tobacco, seriously affects oral health as well as general health. The most significant risk is for oral cancer and pre-cancer. It is also the most common risk factor for periodontal disease.

In 2019, amongst adults in the UK:

- 14.1% were current smokers (6.9 million) with the population of England reporting lower levels (13.9%) compared with Northern Ireland (15.6%) Wales (15.5%) and Scotland (15.4%)

- 15.9% of men smoked compared with 12.5% of women

- younger adults (aged 25 to 34 years) continued to have the highest proportion of current smokers (19.0%)

- prevalence was 2.5 times higher in people in routine and manual occupations than in people in managerial and professional occupations: whereas around 1 in 4 people (23.2%) in routine and manual occupations smoked, compared with just 1 in 10 people (10.2%) in managerial and professional occupations

- since 2014, there have been statistically significant declines in the proportion of current smokers among all socio-economic groups; however, inequalities have increased

- most people take up smoking in their teens or early twenties

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2020.

The prevalence of smoking also varies within countries, and changes over time so it may be helpful to check local rates for your area as listed in the resources at the end of this section.

Smoking rates in people with alcohol and other drug dependencies are 2 to 4 times those of the general population (4).

Smokers are less likely to report having very good health (3), when compared with those who have never smoked (1, 5); reporting bad or very bad general health was more than 2.5 times as common in current smokers than those who have never smoked (12.2% and 4.7%, respectively) (5).

In Great Britain, more than half (52.7%) of people aged 16 years and above who currently smoked said they wanted to quit and 62.5% of those who have ever smoked said they had quit (1). Most cigarette smokers report that they would like to stop and make many attempts to quit. Currently, around half of all smokers quit using willpower alone (6). However, receiving support can greatly increase a person’s chances of quitting successfully.

People are 3 times as likely to quit successfully if they use a combination of stop smoking aids (including e-cigarettes) together with specialist help and support (6, 7).

Supporting smokers in contact with the healthcare system to quit is a prevention priority in the NHS Long Term Plan and every health care professional has a role to play (8 to 10).

Recent research evidence has focused on interventions during hospital care. A Cochrane Review by Rigotti and others (11) found that hospital based stop smoking interventions that begin during a hospital stay and include counselling with follow-up support for at least one month after discharge are effective in increasing quit rates. Such programmes are effective when administered to all hospitalised smokers, regardless of their reason for admission. Adding nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to a counselling programme increases the success rate of a programme for hospitalised smokers (11). Hospital based programmes that include behavioural support, pharmacotherapy and follow-up have also been shown to reduce all-cause re-admissions and mortality at one and 2-year follow-up (12).

As many of the adverse effects of tobacco use on the oral tissues are reversible, stressing their impact on oral health may provide a useful means of motivating patients to quit. Quitting smoking is the best thing a smoker can do for their health, and the benefits of stopping begin almost immediately.

The greatest benefits to oral health relate to preventing periodontal diseases (Chapter 5) and oral cancer (Chapter 6). The most significant harms of tobacco use on the oral cavity are oral cancers and pre-cancers, increased severity and extent of periodontal diseases, tooth loss and poor wound-healing post-operatively (13, 14). Reducing tobacco use is a key priority for the NHS across the 4 nations of the UK.

Chewing tobacco and other tobacco products

Dental team members should be aware of the various alternative forms of tobacco and alternative forms of use such as chewing rather than smoking and that these are associated with oral cancer, other oral pathologies and negative health effects (15). Data on the use of other tobacco products within the UK is more limited than smoking; however, a recent oncology paper highlights that the use of smokeless tobacco is becoming a global concern (16). Smokeless tobacco is responsible for a large number of deaths worldwide with the South East Asian region bearing a substantial share of the burden (17).

The use of betel quid (paan) with areca nut, with or without the addition of smokeless tobacco, is especially common within South Asian culture and mouth cancer is very common in the Indian sub-continent (18). Its social and cultural use is observed across the UK (19), with some evidence that it is impacting on the risk of oral cancer (20, 21).

Shisha smoking (also known as hookah, water pipe, narghile or hubble bubble) is a traditional method of tobacco use, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean region, but its use is observed across the world. Many people wrongly perceive waterpipe smoking as less harmful than smoking because of the perception that water filters out the harmful substances in the smoke. However, it’s associated with many of the same risks as cigarette smoking. Like smoking, shisha smoking produces significant levels of noxious chemicals including tar, carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide and various carcinogens (22, 23).

Nasal snuff made from pulverised tobacco leaves is a dry form of tobacco which is inhaled or ‘snuffed’ into the nasal cavity. Moist snuff typically used in Scandinavia is known as Snus. Snus can be loose or pre-packaged in small teabag-like sachets. Other countries have different forms of dried or moist tobacco used for sniffing, dipping or chewing (24, 25). Chewed tobacco comes in a number of forms, loose-leaf, dip, plug, twist and chew bags.

New products are continually emerging such as ‘Heat-not-burn’ tobacco products (HnB); these are electronic devices that heat process tobacco instead of combusting it to supposedly deliver an aerosol with fewer toxicants than in cigarette smoke (26). Evidence is primarily drawn from tobacco industry data and lacks research on long-term HnB use effects on health (26).

All forms of tobacco that are legal in the UK present an oral cancer risk and users of tobacco in any form can be helped to quit through smoking cessation interventions (27 to 29). It’s important to ask people if they use smokeless tobacco, using the names that the various products are known by locally. If necessary, show them a picture of what the products look like, using visual aids (28) as shown below (Figure 11.1), or by using this link.

Common names for products containing tobacco include:

- waterpipes, shisha, hookah, hubble-bubble (containing tobacco and flavourings)

- zarda (tobacco often added to paan)

- gutkha (processed tobacco with added sweeteners)

- scented chewing tobacco (tobacco with added flavours)

- naswar, nas, niswar (tobacco with slaked lime, indigo, cardamom, oil, menthol, water)

- chillam (heated tobacco)

- paan (tobacco, areca nut or ‘supari’, slaked lime, betel leaf)

- snuff, snus (powdered or ground tobacco)

- khaini (tobacco, slaked lime paste, sometimes areca nut)

This may be necessary if the person’s first language does not include English or if the terms are unfamiliar. Although there has been less research on smokeless tobacco use, a similar approach to delivering very brief advice is recommended (Table 2.3) for patients who are users (30). Advising of the health risks, using the same brief intervention and referring patients who want to quit to specialist support services is recommended. The outcome then needs to be recorded in the patient notes, as with all tobacco use.

Effective interventions to support patients to quit smoking

Healthcare practitioner advice, provided across a variety of healthcare settings, helps people stop smoking (31).

Research suggests that 95% of patients expect to be asked about smoking and a short intervention can make all the difference (32). Smokers are more likely to expect to be asked about tobacco use and recognise the need to change than people with other risk behaviours (33).

Dental teams are in a unique position to provide opportunistic advice to many ‘healthy’ people who need professional support to stop their tobacco use and reduce their risk of oral disease. The first stage is to establish if the patient is a smoker, of any form of tobacco. Dental teams across primary care, community and hospital services routinely investigate tobacco use as part of standard patient care. Advice can then be given about effective methods of quitting smoking involving behavioural and pharmacological approaches as outlined in Figure 11.2: Very brief advice pathway: 30 second discussion.

Very Brief Advice

Very Brief Advice (VBA) from the dental team (28, 29, 34), as outlined in the evidence tables (Chapter 2, Table 3), has been shown to increase a patient’s motivation to quit and can double a patient’s success with quitting smoking (28, 29). Dental professionals can successfully deliver tobacco cessation interventions to increase the chances of achieving long‐term tobacco‐use abstinence; this includes single and multi‐session behavioural support, and behavioural support with the addition of NRT or e‐cigarettes (29). Many people will, however, need VBA on a number of occasions before they are ready to act. Keep asking and advising because it will make a difference (35).

Ask about smoking

All patients (adolescents and adults) should have their smoking status (current smoker, ex-smoker, never smoked) established at the beginning of a course of dental care, recorded, and checked at every opportunity. This is part of a normal medical history routine in a dental setting and should be explored during the consultation.

Do you smoke?

The member of the dental team who elicits this information should ensure this information is recorded in the patient’s clinical notes.

For those with or at risk of oral disease, most notably oral cancer, pre-cancer or periodontal disease, due to smoking or tobacco use, it is important to give VBA.

Advise on the best way of quitting

Inform patients that the best way of quitting is with a combination of specialist support and medication (36).

Advice involves making a simple statement such as:

The best way to stop smoking is with a combination of behavioural support and stop smoking aids, which can significantly increase the chance of stopping.

Medications that improve the chances of adults quitting smoking include combination nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline, and bupropion (37 to 40).

E-cigarettes or vapes are not risk free but are far less harmful than cigarettes and there is growing evidence that they can help smokers to stop smoking (41 to 43).

The traditional approach to advice has been to warn a smoker of the dangers of smoking and advise them to stop. This is deliberately left out of VBA for 2 reasons: first, it can immediately create a defensive reaction and raise anxiety levels and, second, it takes time and can generate a conversation about smoking use, which is more appropriate during a dedicated stop smoking consultation.

Act according to the patient’s motivation

For those who wish to stop, refer to specialist support services where these are available (42). If not available, it will be important to actively refer (not signpost) them to their GP or pharmacist:

Would you like me to refer you for specialist stop-smoking advice and support?

For those who are not ready to stop, affirm that this opportunity will remain open to them with:

That is fine, but help is available. Let me know if you change your mind.

A summary of the smoking-pathway, which is useful for all forms of tobacco, is presented in Figure 11.2.

Harm reduction

Ceasing smoking reduces harm, ideally stopping permanently, or temporarily for example preceding an operation. Other people may reduce in stages and then stop. People who are not ready or willing to stop smoking completely may wish to consider using a nicotine-containing product to help them reduce their smoking en route to harm reduction. Dental team members should familiarise themselves with the NICE guidance on Smoking: harm reduction (44) and the recommendations in NICE Guidance NG92 (42. Almost all of the harm from smoking is caused by other components in tobacco smoke, not by the nicotine. Smoking is highly addictive, largely because it delivers nicotine very quickly to the brain and this makes stopping smoking difficult. Nicotine-containing products are an effective way of reducing the harm from tobacco for both the person smoking and those around them. It is less harmful to use alternative nicotine-containing products than to smoke (40).

Local services

Expert support from local stop smoking providers, combined with the use of stop smoking aids gives smokers the best chance of quitting for good. Depending on the area, services can be based in a range of settings including integrated lifestyle services, community pharmacies and GP surgeries further information can be found on the NHS website.

Stop smoking support is free (with the exception of prescription charges where applicable) and offers a choice of one-to-one or group behavioural support from a trained stop smoking advisor together with pharmacotherapy. Smokers who receive this package of support are 3 times as likely to quit successfully as those who try to quit unaided or with over the counter NRT.

Dental team members should find out what specialist stop smoking providers (ideally local stop smoking support) are available locally for their patients. Referral to local providers for support can be made quicker and easier by adding a template into your existing data management system.

Where none is available then patients should be directed towards their GP or pharmacist. Furthermore, it is helpful to be aware if there are specific local programmes such as voucher schemes for pregnant women to stop smoking, given that dental care is free during pregnancy this presents an ideal opportunity to support smoking cessation. A trial conducted in one centre showed that women in Glasgow were 2.63 times more likely not to be smoking at the end of pregnancy when incentives were provided for supported smoking cessation (45).

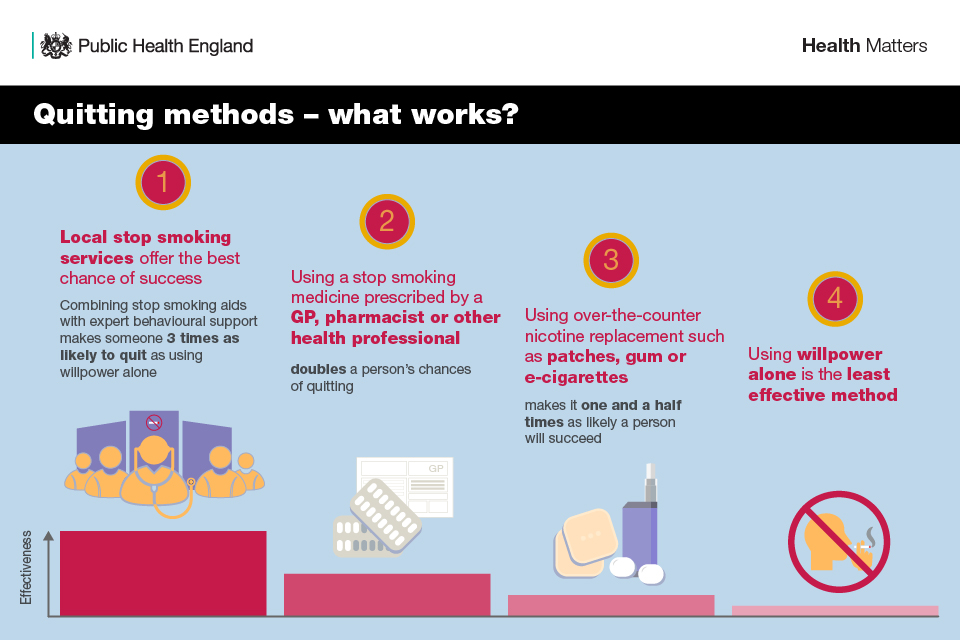

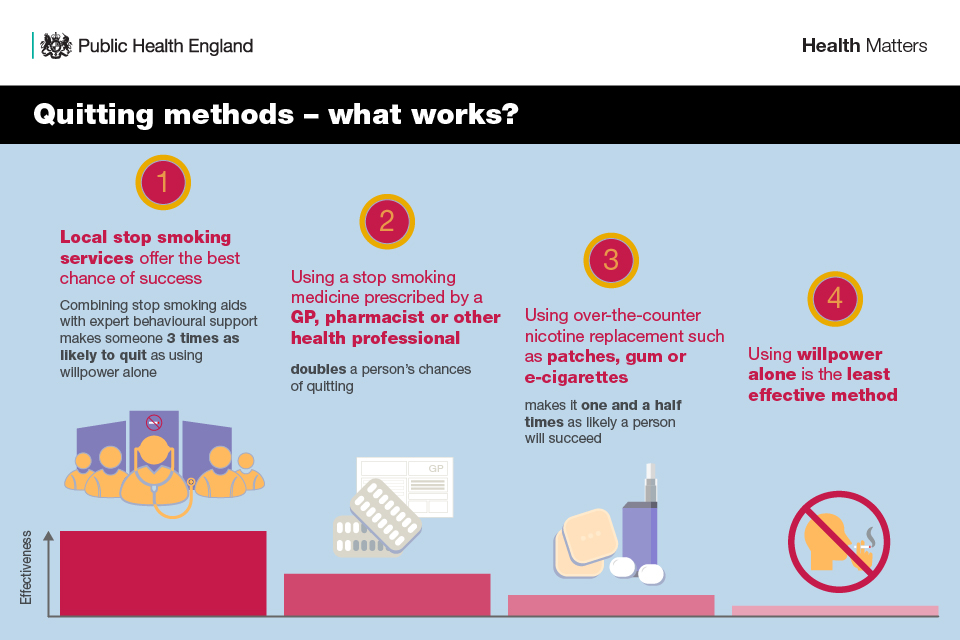

Overview of quitting methods

1. Local stop smoking services

They offer the best chance of success. Combining stop smoking aids with expert behavioural support makes someone 3 times as likely to quit as using willpower alone.

2. Using a stop smoking medicine

A stop smoking medicine prescribed by a GP, pharmacist or other health professional doubles a person’s chances of quitting.

3. Using over-the-counter nicotine replacement

NRT such as patches, gum or e-cigarettes makes it one and a half times as likely a person will succeed.

4. Using willpower alone

This is the least effective method.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy is particularly effective when used in conjunction with behavioural support. Many of these products are available over the counter in a pharmacy or other retail outlets.

Most of the research involves adults and is related to cigarette smoking. Whilst the dental team may not be involved in prescribing these products, patients may choose to either obtain them elsewhere on prescription or purchase them. So it is helpful to be aware of the evidence and to boost patients’ confidence in using them.

NRT, varenicline and bupropion have all been shown to improve the chances of quitting smoking in adult smokers.

Evidence suggests that:

- combination NRT (a patch combined with a fast-acting product) or varenicline are equally effective as quitting aids (38)

- all of the licensed forms of NRT (gum, transdermal patch, nasal spray, inhalator and sublingual tablets or lozenges) can help people who make a quit attempt to increase their chances of successfully stopping smoking. NRTs increase the rate of quitting by 50% to 60%, regardless of setting (46)

- combination NRT is more effective with regard to long term quit rates than a single form of NRT in adults who are motivated to quit (39)

- higher dose (21 mg/24-hour) nicotine patches result in higher quit rates than lower dose (14 mg/24-hour) nicotine patches in those motivated to stop smoking (39)

- there is no evidence of a difference between fast-acting NRT, such as gum and lozenge, and nicotine patches in those motivated to stop smoking (based on high quality evidence) (39)

- varenicline may be more effective than bupropion with regard to quit rate and relapse (37)

- varenicline improves abstinence compared with bupropion or NRT, however it is more likely than placebo to lead to nausea, insomnia, abnormal dreams, headaches and serious adverse events. The lack of comparative adverse effects assessment of varenicline with bupropion or NRT means that firm conclusions of the overall comparative effects of these interventions cannot be drawn (47)

- NRT may increase the chances of quitting during pregnancy however, evidence is low certainty (48). There is no evidence that NRT is harmful in pregnancy and licensed NRT medication is routinely used to aid cessation

Whilst patients may be prescribed varenicline or bupropion, the drug of choice is most likely to be varenicline unless there are medical contra-indications (49). Varenicline reduces cravings for nicotine by blocking the reward pathway and by reinforcing effects of smoking which take place in the brain (50). Bupropion (Zyban) reduces urges to smoke and helps with withdrawal symptoms (50).

Considering the specific safety concerns, contraindications (for example, bupropion is contraindicated in patients who have seizures), and comorbidities, the choice of agent is based largely on patient preference after discussion with a clinician (49). Current evidence suggests that adverse events for these interventions are mild and would not mitigate their use, although concerns have been raised that varenicline may slightly increase cardiovascular events in people already at increased risk of these illnesses (37, 38).

There is a growing body of evidence evidence that behavioural interventions combined with nicotine replacement, provided by dental professionals, may increase tobacco abstinence rates in cigarette smokers (29).

Clinical trials have largely been conducted among adults; thus, in children, there is no evidence to support the use of pharmacological interventions (51). NRT is licensed for use in children over 12 years of age in the UK.

Reducing smoking

If a patient indicates interest in cutting down their smoking, the healthcare professional should inform them that health benefits come from stopping smoking altogether. Any benefits of simply reducing are unclear.

However, the clinician should advise them that if they reduce their smoking now, they are more likely to stop smoking in the future, particularly if they use licensed nicotine-containing products to help reduce the amount they smoke (40).

People who reduce the amount they smoke without supplementing their nicotine intake with a licensed nicotine product tend to compensate by drawing smoke deeper into their lungs, exhaling later and taking more puffs. Therefore, use of a licensed nicotine-containing product to provide ‘therapeutic’ nicotine is recommended.

Alongside the strong safety profile of NRT, the benefits of advising smokers unwilling or unable to quit smoking to reduce their smoking using NRT are likely to outweigh any disadvantages, given that the alternative is likely to be no action (40).

The Stoptober campaign during the month of October provides an opportunity for smokers to quit, as people who stop smoking for 28 days are 5 times more likely to quit for good (52).

Safety of nicotine: evidence and misconceptions

While nicotine is the addictive substance in cigarettes, it is relatively harmless (9).

In fact, almost all of the harm from smoking comes from the thousands of other chemicals in tobacco smoke, many of which are toxic.

Despite this, research finds that among smokers and ex-smokers in the UK (22):

- only 6 in 10 think that NRT is less harmful than smoking cigarettes

- only 4 in 10 incorrectly think nicotine in cigarettes causes most of the smoking-related cancer

Given these misconceptions, advising smokers on the relative safety of nicotine containing products compared to smoked tobacco is an integral part of supporting them to quit.

People should be advised to use NRT, or an e-cigarette if they choose as it will help them to manage their cravings when they stop smoking.

Vaping (e-cigarettes)

E-cigarettes, also known as vapes, are the most popular stop smoking aid in England, with 2.5m users in 2019 (9, 53).

There are many different types of e-cigarette product and this market is rapidly changing.

E-cigarettes are electronic devices that heat a liquid, usually containing nicotine, to create an aerosol for inhalation. At present, there is no medicinally licensed e-cigarette product available on the UK market. However, the UK has some of the strictest regulation for e-cigarettes in the world. Under the Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 (54), e-cigarette products are subject to minimum standards of quality and safety, as well as packaging and labelling requirements to provide consumers with the information they need to make informed choices.

All e-cigarette products must be notified by manufacturers to the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), with detailed information including the listing of all ingredients. Leading UK health and public health organisations including the Royal College of General Practice, British Medical Association and Cancer Research UK now agree that although not risk-free, e-cigarettes are far less harmful than smoking (50).

Only a very small proportion of young people, who have never smoked, report that they vape (<1%) (55). More than half of current vapers have managed to stop smoking completely and it is estimated that e-cigarettes may help over 50,000 smokers a year in England to quit smoking, who would not have done so by other means (56).

E-cigarettes are particularly effective when combined with a structured programme of behavioural support. A major UK clinical trial found that, when combined with expert face-to-face support, people who used e-cigarettes to quit were twice as likely to succeed than people who used other nicotine replacement products such as patches or gum (57). People who have completely switched to vaping should be recorded as non-smokers in dental records.

NICE guidance NG92 (42) sets out the following recommendations for health and social care workers in primary and community settings.

For people who smoke and who are using, or are interested in using, a nicotine-containing e‑cigarette on general sale to quit smoking, explain that:

- although these products are not licensed medicines, they are regulated by the Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 (54)

- many people have found them helpful to quit smoking cigarettes

- people using e‑cigarettes should stop smoking tobacco completely, because any smoking is harmful

- the evidence suggests that e‑cigarettes are substantially less harmful to health than smoking but are not risk free

- the evidence on e-cigarettes is still developing, including evidence on their long-term health impact

In summary, there is growing evidence that e-cigarettes are helping many thousands of smokers in England to quit. The available evidence from research trials suggests that their effectiveness is broadly similar to prescribed stop smoking medicines and better than NRT products if these are used without any professional support. E-cigarettes are particularly effective when combined with expert help from a local stop smoking service.

Implementation and delivery in dental practice

The National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) has developed a simple form of advice designed to be used opportunistically in less than a minute in almost any consultation with a smoker.

All dental team members should be encouraged to undertake the NCSCT training as part of regular continuing professional development, therefore ensuring all dental team members are competent to deliver VBA and brief interventions in smoking cessation.

The most common intervention dental teams will be involved in is delivering ASK, ADVISE, ACT in line with VBA to smokers (Figure 11.2). Use of the evidence-informed pathway will increase the chance of a successful quit attempt. It just takes 30 seconds and can give patients the motivation to gain professional help which will increase their chances of quitting. It is important to be aware of policies, services and routes of access in your local healthcare system as these vary across the UK. A similar approach can be followed with all tobacco users.

The best outcomes occur when those who are interested in stopping take-up a referral for specialist support. Timing is crucially important: the quicker the contact by a local stop smoking service, the greater the motivation and interest from the individual. Dental patients who express a desire to stop should be referred to their local specialist stop smoking support (ideally a local stop smoking service) to receive the best opportunity to stop smoking.

Dental teams and the local stop smoking services can work collaboratively in a variety of ways. As a first step, it’s important that all members of a dental team are fully aware of the services offered locally and of how these operate. Arranging a meeting with a representative of a local provider could provide a useful opportunity for dental teams to learn about the service offer and the best ways of referring dental patients.

It’s important that no matter who makes the referral, the patient’s progress in stopping is assessed and is recorded in their clinical notes at each subsequent dental appointment.

Stopping tobacco use can be a difficult process and is often associated with a range of unpleasant, short-term withdrawal symptoms, some of which, such as ulcers, directly affect the oral cavity.

Reassurance and advice from dental team members may help patients deal more effectively with these problems, thereby increasing their chances of quitting successfully.

The Cochrane review on tobacco cessation interventions (58) provided during substance abuse treatment or recovery is particularly helpful in managing patients who may have more than one addiction. Current evidence suggest that providing tobacco cessation interventions targeted to smokers in treatment and recovery for alcohol and other drug dependencies increases tobacco abstinence.

Resources

NCSCT Very Brief Advice on Smoking for Dental Patients.

e-Learning for healthcare: Alcohol and Tobacco Brief Interventions programme.

Find your Local Stop Smoking Service (LSSS).

Smoking and tobacco: applying All Our Health.

Health matters: stopping smoking – what works?.

Stop smoking options: guidance for conversations with patients.

E-Cigarettes policy, regulation and guidance.

Local Tobacco Control Profiles.

The case for delivering Very Brief Advice on smoking YouTube video:

References

1. Office of National Statistics. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2019. London: ONS; 2020 7 July 2020.

2. Centre for Disease Control. Health Effects of Secondhand Smoke. CDC; 2020 [updated 27 February 2020].

3. NHS Digital. Statistics on Women’s Smoking Status at Time of Delivery, England – Quarter 3, 2017 to 2018](https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-women-s-smoking-status-at-time-of-delivery-england/statistics-on-women-s-smoking-status-at-time-of-delivery-england-quarter-3-2017-18). NHS Digital UK; 2018 [updated 10 May 2018].

4. Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co‐morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal on Addictions 2005;14:106‐

5. ONS. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2018. London: Office for National Statistics; 2 July 2019.

6. Public Health England. Health matters: stopping smoking – what works? London: PHE; 17 December 2019.

7. NHS. Quit smoking.

8. NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan. London: NHS England; 2019 [updated 7 January 2019].

9. UK Government. E-cigarettes and heated tobacco products: evidence review. In: Care DoHaS, editor. [edited 2 March 2018] London: UK Government; 2018.

10. NICE. Making every contact count. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2021 [24 April 2021].

11. Rigotti NA, Clair C, Munafò MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012(5).

12. Mullen KA, Manuel DG, Hawken SJ, Pipe AL, Coyle D, Hobler LA and others. Effectiveness of a hospital-initiated smoking cessation programme: 2-year health and healthcare outcomes. Tobacco Control. 2017;26(3):293-9.

13. Johnson NW, Bain CA. Tobacco and oral disease. British Dental Journal. 2000;189(4):200-6.

14. Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, Boccia S, Castellsague X, Chen C and others. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2009;18(2):541-50.

15. Gupta B, Johnson NW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of association of smokeless tobacco and of betel quid without tobacco with incidence of oral cancer in South Asia and the Pacific. PloS one. 2014;9(11):e113385.

16. Mehrotra R, Yadav A, Sinha DN, Parascandola M, John RM, Ayo-Yusuf O and others. Smokeless tobacco control in 180 countries across the globe: call to action for full implementation of WHO FCTC measures. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(4):e208-e17.

17. Sinha DN, Suliankatchi RA, Gupta PC, Thamarangsi T, Agarwal N, Parascandola M and others. Global burden of all-cause and cause-specific mortality due to smokeless tobacco use: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tobacco control. 2018;27(1):35-42.

18. Gupta PC, Arora M, Sinha D, Asma S, Parascondola M. Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health in India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016.

19. Panesar SS, Gatrad R, Sheikh A. Smokeless tobacco use by south Asian youth in the UK. The Lancet. 2008;372(9633):97-8.

20. Csikar J, Aravani A, Godson J, Day M, Wilkinson J. Incidence of oral cancer among South Asians and those of other ethnic groups by sex in West Yorkshire and England, 2001–2006. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2013;51(1):25-9.

21. Tataru D, Mak V, Simo R, Davies EA, Gallagher JE. Trends in the epidemiology of head and neck cancer in London. Clinical Otolaryngology. 2017;42(1):104-14.

22. Wilson S, Partos T, McNeill A, Brose LS. Harm perceptions of e‐cigarettes and other nicotine products in a UK sample. Addiction. 2019;114(5):879-88.

23. Perraud V, Lawler MJ, Malecha KT, Johnson RM, Herman DA, Staimer N and others. Chemical characterization of nanoparticles and volatiles present in mainstream hookah smoke. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2019;53(9):1023-39.

24. FDA. Smokeless Tobacco Products, Including Dip, Snuff, Snus, and Chewing Tobacco. Silver Spring, MD: US Food & Drug Administration; 2020 [updated 23 June 2020].

25. World Health Organization IAfRoC. Smokeless Tobacco and Some Tobacco-specific N-Nitrosamines. Lyon, France: WHO IARC; 2007.

26. Simonavicius E, McNeill A, Shahab L, Brose LS. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review. Tobacco control. 2019;28(5):582.

27. Maziak W., Jawad M., Jawad S., Ward K.D., Eissenberg T., Asfar T. Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(7).

28. Carr AB, Ebbert J. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012(6).

29. Holliday R, Hong B, McColl E, Livingstone-Banks J, Preshaw PM. Interventions for tobacco cessation delivered by dental professionals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021(2).

30. NICE. Smokeless tobacco: South Asian communities. Public Health Guideline [PH39]. London: NICE; 2012 02.10.2010. Contract Number: PH39.

31. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K and others. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:Cd000146.

32. Slama KJ, Redman S, Cockburn J, Sanson-Fisher RW. Community Views About the Role of General Practitioners in Disease Prevention. 1989;6(3):203-9.

33. Brotons C, Bulc M, Sammut MR, Sheehan M, Manuel da Silva Martins C, Björkelund C and others. Attitudes toward preventive services and lifestyle: the views of primary care patients in Europe. The EUROPREVIEW patient study. Family Practice. 2012;29 (supplement 1):i168-i76.

34. Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, West R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2012;107(6):1066-73.

35. NHS England, Health Education England, Public Health England. Alcohol and Tobacco Brief Interventions Programme: NHS England; 2019.

36. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(3).

37. Cahill K, Lindson‐Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(5).

38. Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(5).

39. Lindson N, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Fanshawe TR, Bullen C, Hartmann‐Boyce J. Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(4).

40. Lindson‐Hawley N, Hartmann‐Boyce J, Fanshawe TR, Begh R, Farley A, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(10).

41. Flach S, Maniam P, Manickavasagam J. E-cigarettes and head and neck cancers: A systematic review of the current literature. Clinical otolaryngology: official journal of ENT UK. 2019;30.

42. NICE. Stop smoking interventions and services [NG92]. London: NICE; 2018 28.03.2018. Contract No.: NG92.

43. Hartmann‐Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Stead LF, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(9).

44. NICE. Smoking: harm reduction PH45. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence; July 2013.

45. Tappin D, Bauld L, Purves D, Boyd K, Sinclair L, MacAskill S and others. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2015;350:h134.

46. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(5).

47. Bunt C. How does varenicline compare with bupropion or nicotine‐replacement therapy for smoking cessation? Cochrane Clinical Answers. 2017.

48. Claire R, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Berlin I, Leonardi‐Bee J and others. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020(3).

49. Rigotti N. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults 2020 [updated 27 February 2020].

50. UK Government. Smoking and tobacco: applying All Our Health. London: UK Government; 2020 [updated 16 June 2020].

51. Fanshawe TR, Halliwell W, Lindson N, Aveyard P, Livingstone‐Banks J, Hartmann‐Boyce J. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(11).

52. NHS. STOPTOBER: quit smoking with Stoptober. London: NHS; 2019 [updated 3 April 2018].

53. McNeill A., Brose L., Calder R., Bauld L, Robson D. Vaping in England: an evidence update including mental health and pregnancy, March 2020. London: Public Health England; 2020.

54. HM Government. The Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016. London: Public Health England,; 2016. Contract Number: SI507.

55. McNeill A, Brose L, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D. Vaping in England: an evidence update February 2019. London: Public Health England; 2019.

56. Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brown J. Association of prevalence of electronic cigarette use with smoking cessation and cigarette consumption in England: a time–series analysis between 2006 and 2017. Addiction. 2020;115(5):961-74.

57. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisal N and others. A Randomized Trial of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine-Replacement Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(7):629-37.

58. Apollonio D, Philipps R, Bero L. Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance use disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(11).